A Day in the Life of Willem Ei, and a Cosmological Proof of the Ultimate,

1998, dec. 1999 © by Alfred Scheepers,

Isagoge

That evening, since a friend persuaded him, Willem Ei attended a lecture by Richard Rorty. Afterwards in Amsterdam’s Arti et Amicitiae his alterego was invited to contribute to the present ‘Festschrift’. On his way to the bar he found Richard Rorty inescapably on his way. He remembered what his mother taught him about pragmatists: ‘Address them if you cannot avoid them’. As ‘truth’ had been the topic of the lecture, he raised the point that it may not be scientifically settled what is true or not, but that we can clarify the meaning of our talk about truth. ‘Bulshitt’ said Rorty, his way of saying that in the pragmatist world-view you may be able to clarify butter but not meaning. If this is so, Wlllem thought, in this age of worldwide academic bankruptcy it is probably better to raze down the universities than to use criticism.

That evening, since a friend persuaded him, Willem Ei attended a lecture by Richard Rorty. Afterwards in Amsterdam’s Arti et Amicitiae his alterego was invited to contribute to the present ‘Festschrift’. On his way to the bar he found Richard Rorty inescapably on his way. He remembered what his mother taught him about pragmatists: ‘Address them if you cannot avoid them’. As ‘truth’ had been the topic of the lecture, he raised the point that it may not be scientifically settled what is true or not, but that we can clarify the meaning of our talk about truth. ‘Bulshitt’ said Rorty, his way of saying that in the pragmatist world-view you may be able to clarify butter but not meaning. If this is so, Wlllem thought, in this age of worldwide academic bankruptcy it is probably better to raze down the universities than to use criticism.

Next morning, after breakfast Willem Ei started flossing his teeth. Something got stuck between two molars. After spending two hours and two hundred yards of floss, he started to lament the human con dition, especially since he had an appointment within half an hour. He cursed the God who had created the world for the sole reason to torture him, using such terminology as would have made a pious catholic bystander make a cross, and flee speedily away from the doomed spot that witnessed the pinnacle of blasphemy.

Putting the floss in his pocket, Willem went to meet his appointment. Being too late, the other party was later yet, and there remained ample time to spend another 200 yards of floss during waiting. He already in despair had decided to phone the dentist, when he experienced a change of mind. Abandoning the two maledicted molars, he started flossing the other teeth without encountering any noticeable obstacles. Nearing closer and closer to the two inauspicious molars, he tried again. And, miracle of miracles, the floss dropped between the molars without wriction. And while a moment earlier Willem had cursed the God of Dutch institutional religion (the God who created the sun on the fourth day without considering that to be able to count four days you first should create a sun), his heart now praised the God of the covenant.

Absurd as the story may be, it refers to a religious sense to be found in all ages among all peoples. In his colloquy with the gods Willem never for a moment considered their existence, probably because in things that concern the human heart the notion of ‘existence’ is o f little importance, since the ‘existence’ of the phenomena in this realm coincides with their appearance. ‘God’ is the ultimate concern of the human heart. Defined in this way, to deny God is to deny all values. But what if you are unacquainted with this dimension of ‘ultimate concern’ for the inner recesses? Then it becomes a matter of life and death whether ‘it’ exists or not. ‘To be or not to be’ that’s the question, and we will not let reduce this question to a level of mere psychology. Does God exist or does he not? Someone – probably a fellow contributer to this volume – lately argued that the better arguments are against the assumption, denouncing all who try to circumvent the question of ‘be’ or ‘not be’ as examples of theological cowardice. But first: it is logically impossible to affirm the existence or non-existence of anything whose essence is not defined. If someone asks us whether there is some milk in the fridge, it will not be to difficult to answer with ‘yes’ or ‘no’. We use the verb ‘exist’ meaningfully only when we want to decide the question whether something is located somewhere. When we want to decide the question of ‘existence’ in the widest possible sense, we mean as much as: is something of such and such a nature somewhere located in the universe? If God, as many theologians hold, transcends the universe, it implies, that at least to that essential extent, he cannot be located in it, and ergo to th at essential extent does not ‘exist’. But not only with respect to location, conceptually too ‘God’ is not on a par with a bottle of milk. In the latter case we know what we talk about. But saying ‘God’ we generally cannot explain what we mean. Therefore the proposition ‘does God exist?’ is fairly equivalent to the proposition ‘does X exist’? Whereby the answer depends on how you substitute X. Therefore the discussion about the existence of God conceived as a conceptual entity is an insipid debate.

Absurd as the story may be, it refers to a religious sense to be found in all ages among all peoples. In his colloquy with the gods Willem never for a moment considered their existence, probably because in things that concern the human heart the notion of ‘existence’ is o f little importance, since the ‘existence’ of the phenomena in this realm coincides with their appearance. ‘God’ is the ultimate concern of the human heart. Defined in this way, to deny God is to deny all values. But what if you are unacquainted with this dimension of ‘ultimate concern’ for the inner recesses? Then it becomes a matter of life and death whether ‘it’ exists or not. ‘To be or not to be’ that’s the question, and we will not let reduce this question to a level of mere psychology. Does God exist or does he not? Someone – probably a fellow contributer to this volume – lately argued that the better arguments are against the assumption, denouncing all who try to circumvent the question of ‘be’ or ‘not be’ as examples of theological cowardice. But first: it is logically impossible to affirm the existence or non-existence of anything whose essence is not defined. If someone asks us whether there is some milk in the fridge, it will not be to difficult to answer with ‘yes’ or ‘no’. We use the verb ‘exist’ meaningfully only when we want to decide the question whether something is located somewhere. When we want to decide the question of ‘existence’ in the widest possible sense, we mean as much as: is something of such and such a nature somewhere located in the universe? If God, as many theologians hold, transcends the universe, it implies, that at least to that essential extent, he cannot be located in it, and ergo to th at essential extent does not ‘exist’. But not only with respect to location, conceptually too ‘God’ is not on a par with a bottle of milk. In the latter case we know what we talk about. But saying ‘God’ we generally cannot explain what we mean. Therefore the proposition ‘does God exist?’ is fairly equivalent to the proposition ‘does X exist’? Whereby the answer depends on how you substitute X. Therefore the discussion about the existence of God conceived as a conceptual entity is an insipid debate.

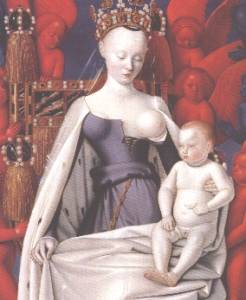

Jean Fouquet, Madonna

To my opinion there can be no meaningful discussion about ‘God’ apart from the sphere of human values, the opposition between ‘good’ and ‘evil’. And here we are back at Willem Ei’s two Gods, which formerly would clearly have been distinguished as the merciful Father vs. his perpetual antagonist, the devil. But since modern theology has made of these two characters two provinces of God’s inner diversity, Willem’s mind is bound to confusion.

But because no theologian as theologian can ever be finally satisfied with a like de-ontification of the religious sphere, I will not end without some exercise in (theo)logical gymnastics. It is a modern version of the ‘cosmological proof’. Of course it is extremely easy to dismiss such an argument ation solely on the ground of social status or academic authority. About 2000 years ago the Buddhist monk Nagasena asked king Menander whether he wanted to discuss like a king or as a philosopher. Menander chose the latter. But who wants to enter upon the following argument instead of simply barking at it; to him I wish good luck.

Demonstratio

The Law of Entropy

Modern Physics has accepted the law of entropy as its basic law. That means: all energy tends to devaluate to the level of warmth. Therefore the universe left to itself will finally freeze to death, for a limited amount of warmth spread over a vast universe is very cold indeed. The law of entropy therefore states that one day all life will end, everything in the universe will be nivellated and spread evenly through space, and in the final nirvana will rest in peace forever.

The existence of life does not seem to be very much in accord with this entropic principle. If the world did originate from a big bang, as physicists want us to believe, and the matter originating from this primordial explosion from the outset was subject to the law of entropy, it requires a clever mathematician to explain the forms of life and organization that we actually are confronted with. Under the law of entropy it is principally impossible that a state of differentiation emerges from an un differentiated primary state.

Therefore physicists have adopted a counter-law. The law of entropy, it is suggested, is counteracted by a law that commands energy to upgrade up to the level of the highest forms of intelligence, thus creating human life and maybe even God. But if this law exists, the law of entropy cannot be valid, and if the law of entropy is universally valid, its opposite cannot be true at the same time and in the same respect. This means, if either one of these laws is universally valid, the other must be untrue, and if both may have a claim of validity, neither of the laws can be universally valid. Here physics should bow before the higher jurisdiction of logic.

As both phenomena, degeneration of energy and the existence of highly complex forms of organization (be it in the forms of life or otherwise) are actually observed, it must be true that neither of the laws is universally valid. As we know that the law of entropy was first used to describe the behaviour of gasses in a closed space, we at the same time know the limitation under which the entropic law alone is valid: in a closed energetic system. The observation of phenomena that contradict the entropic law therefore indicates that the universe cannot be a closed system. Therefore the entropic law may be valid only in parts of the universe that can be perfectly isolated. And it can exist only if such cosmic insulae exist and can have only such extent and application as such insulae have. It is possible that such perfect insulae do not exist at all, or that they do exist only approximately, in which case the entropic law has only approximate validity. Then what we consider as entropic phenomena are so only approximately.

Neither can the law of upgrading energy, the organic law, be universally valid. For in that case there would be no explanation for the phenomenon of disintegration. So what we consider as a tendency to higher organization may be valid only if there would be no factor limiting this validity, that is, in a system of absolute openness. But we nowhere observe situations without constrictions.

Therefore my thesis is that the organic principle is limited by the very principle of entropy, and that the principle of entropy is broken up by the very principle of organization. The principles have limited validity not only in physical matters, for every form of existence implies the physical level of existence. Therefore if the physical level is basic to that of life and intelligence, etc., then the laws of physics are equally valid for life and intelligence, etc. We actually observe the same principles in our own social life. Thronged in a crowded subway we tend to keep as much distance as possible to provide for ourselves as much private space as we can get. The outcome of this collective action is an even distribu tion of passengers in the closed subway space. Communication is restricted to the unavoidable and the mob is as undifferentiated as can be. No sign whatever of the formation of social structures. But now the airplane shipwrecked in the desert. In the endlessness of space the survivors keep close together. If someone loses contact with the group chances of survival are next to nihil. Instead of the centrifugal action of the mob in the subway we find the centripetal action of the group in the desert. Best chance of survival is not only to stay together but also to distribute tasks. One sustains a fire, some look for edibles, another on the look-out etc. In the openness of interdependence a social organization is structured. In the subway one is not dependent on the other but oppressed by the others, and for the maintenance of personal identity one embraces the entropic stance. In the desert the organizational pattern is adopted for the sake of the maintenance of the same personal identity. As subatomic particles are just fellow entities that emotionally react in the same way as we do, I want to postulate that, accordingly, (by reason of analogy) both the entropic and organic principles are subspecies of the more universal principle of self-preservation: Every entity tries to perpetuate its own existence, the conatus essendi of Spinoza, the ‘abhinivesha’ of Pata–jali. In fact this principle seems to present a m idway between the entropic and the organic principles, between the deathdrive and the pleasure-principle. But it is not on the same level. When the preservation drive is on one level of any organization, the entropic and organic principles operate on the meta- or sub-level of the same organization as a reaction to this preservation drive. The constituted level is controlled by the preservation drive of the constitutive level. This means that the constitutive level has an impact on the constituted level, as appears from the people in the desert who flock together to form a community; it imposes structure on it, while the constituents themselves integrate into a whole capable of growth. Therefore the openness of the constituted system itself fosters the openness of its constituent parts.

On the other hand, because in a closed system the structure of the constituents themselves undergo a disintegrating impact from the side of the closed constituted system, they, because of their preservation drive, ward of this influence in defence by closing themselves. For example, people in the subway are usually introvert and tacit, because, if they would do otherwise, the mob might molest them. In the same way, each other individual of the mob will refrain from interfering with the drunkard, because they fear agression. So the best way of survival in a closed system seems to be as a closed system. (In a closed society t he best way to survive is not to express your opinions) But, as seen from the example of the survivors in the desert, the best way to preserve the constituents (or constitutive level) in an open system is to let them be open and integrative. (In a democracy you survive by crying out your opinions as loud as possible.) Any organization as far as organization preserves its constituents, and any constraint upon it tends to disintegrate not only the organization but also its constituents. Therefore not only is the whole dependent on the part for its embodiment, but the part is equally dependent upon the whole for its form and (well-)being.

The structures of the constitutive and constituted levels of any organization, accordingly, are closely linked toward each other, and mutually influence one another. While in the open system the constitutive level forces its structure on the constituted level, because it strives for its own preservation, and vice versa the open structure of the constituted level induces the constitutive level to organize, the preservation drive of the constituted level in the closed system tends to impose its limits upon the constituents, transforming them into closed systems themselves or otherwise destroy them. But this very adaptive attitude of the constituents prevents the closed constituted (or meta-) system from breaking open. When the constituted level is closed, it at the same time closes the constituting level, and the closedness of the constitutive level, in turn, preserves the closedness of the constituted or meta-level.

As the closing of a system on a sub-level is induced by the closing of its meta-level system, and no change appears without a cause, then a closing of the meta-level system itself must be induced by the closing of its meta-level system. But as it also appears that the organization of a meta-level is controlled by a self-preservation tendency on sub-level, it follows that any organization on meta-level is controlled by a preservation drive on sub-level. As in a causal system of this type necessarily all values of open/closed on all sub- and meta-levels must be repeated it follows that the ambivalence of openness and closedness cannot occur if they are all causally determined. Therefore, if a bipolarity of entropic and organic tendencies in the universe can be observed, it must needs be that causal determination is not universal, and it is this indetermination that itself must interfere in causality to cause the bipolarity and ambivalence of the phenomenal realm. A like cause must be an ultimate cause. Without such ultimate cause no generation or destruction could ever be, and since such generation and destruction are observed, there must be an ultimate indeterminate cause.

The entropic organic ambivalence of reality makes that any given situation of change of an out of conatus essendi reacting identity can be considered from a double per spective. With respect to its previous state it must be considered as its disintegration, with respect to its next state as its integration. Therefore any system is closed in at least one perspective and open in another perspective, viz the two temporal ones of past and future. Generally, however, there is more than one respect in which a system is bi-perspectival. Consider the knot in the wire of a vacuum-cleaner, which considered as knot is a spontaneous organization, but considered as wire an equally spontaneous disintegration.